Kitsch

Xiaochuang Wang

Kitsch refers to a form of culture that is created primarily to appeal to a mass audience, usually though excessive sentimentality and melodrama. Artists who practice this approach have mastered the art of creating works that appeal to viewers’ sensibilities through a formula determined by the market. Critics like Thomas Kulka and Clement Greenberg have criticized kitsch, dismissing it as aesthetically and artistically worthless. More recently, however, some forms of kitsch have been embraced ironically.

One of the most influential contributors to the analysis of kitsch was the art critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1995), who, in his influential 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” focused on the relationship between mass culture and its avant-garde Other. As he wrote, “Where there is an avant-garde, generally we also find a rear-guard.”1 He classifies kitsch as the opposite of avant-garde art, demonstrated by the examples of popular commercial art and their chromotypes.2 According to Greenberg, kitsch is executed only to gratify popular demand via “vicarious experience and faked sensations.”

Kitsch fails to do what successful avant-garde art does: provide critical insights into its own ideas, processes, and forms of expression.3 Instead, it only mimics the superficial appearance of art. According to Greenberg, kitsch appeals to individuals from lower socio-economic classes, because they do not have the luxury of leisure to cultivate an interest in more challenging forms of culture (thus, a Russian peasant will always prefer the realist kitsch of Repin to an avant-garde work by Picasso).4 For Greenberg, the rise of kitsch was linked to a rise in totalitarian governments; both relied on passive followers who are presented with answers rather than questions. It is only in repressive societies where we find people truly resentful of avant-garde expression, and where governments strategically adopt kitsch as their official cultures.

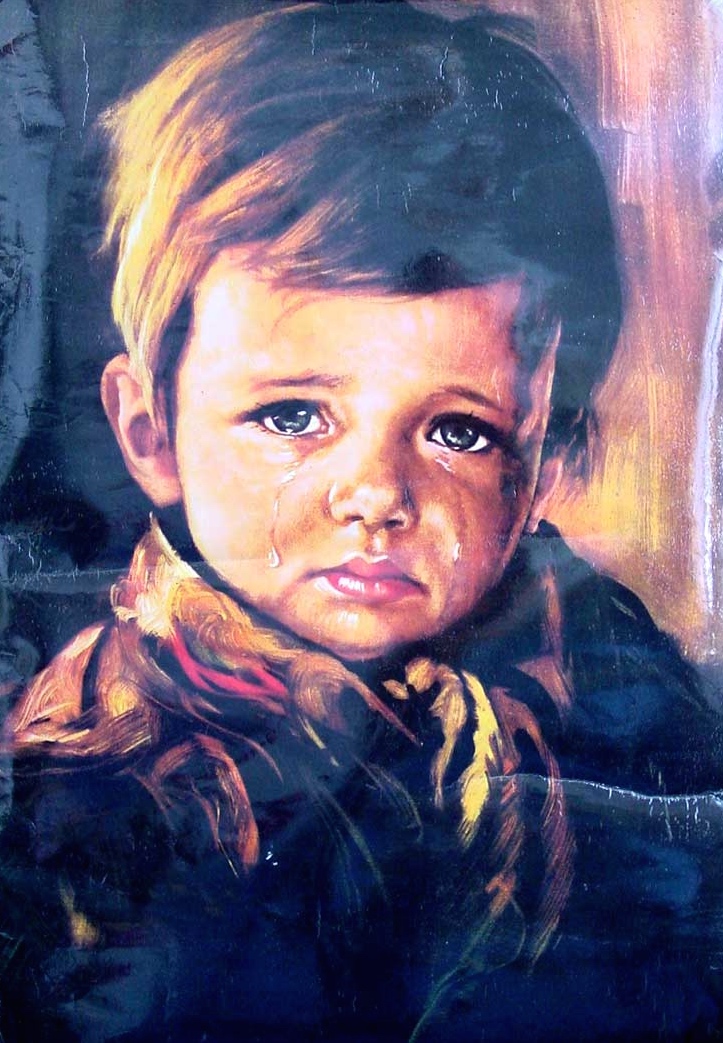

On the morning of September 4th, 1985, the British newspaper The Sun featured a story on the “The Crying Boy Curse,” about a couple who blamed a cheap print of a painting of a crying toddler for the fire that destroyed their home [Figure 1]. The print had escaped unscathed. The original was made by the Spanish artist Bruno Amadio (also known as Giovanni Bragolin) (1911-1981), whose studio reportedly later burned down [Figure 2]. The boy in the painting is an orphan, who ran away after seeing his parents die in a blaze, and who later died because of injuries succumbed in an accident.5 Since then, many believe that reproduction of the paintings (sold in branches of English department stores) are haunted by the boy’s curse. After The Sun covered this story, other newspapers and magazines like The Daily Star, The Daily Mail and The Shropshire Star featured stories on other people who were affected by the curse, which in turn made the painting popular in print media.

Bragolin’s Crying Boy is an example of kitsch because, as Greenberg suggests, it evokes “fake sensations.”6 Further, it fulfills the critic Kulka’s requirement of being figurative, rather than abstract (figurative style are necessary to kitsch in order to evoke said sensations).7 Rather than evincing a pained facial expression, the boy’s tears fall gently down his cherub cheeks, to play on the viewer’s sympathy. The tonal range of the work is dull and flat, and the composition, generic. The painting was not created for self-expressive purposes, but to appeal to the broadest mass market possible. It is perhaps why the story of its “curse” was so easily sensationalized in newspapers and on TV, an example of kitsch generating even more kitsch.

Footnotes

- Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 543.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 546.

- Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 2006), 96-106.

- David Clark, The Curse of the Crying Boy. April 2008. http://drdavidclarke.co.uk/urban-legendary/the-curse-of-the-crying-boy/

- Roger Scruton, “Kitsch and the Modern Predicament,” ( Modern Culture, 2005), 6.

- Thomas Kulka, “Kitsch,” British Journal of Aesthetics 8:1 (Winter 1988): 28.