Gaze

Jasmine Clarke

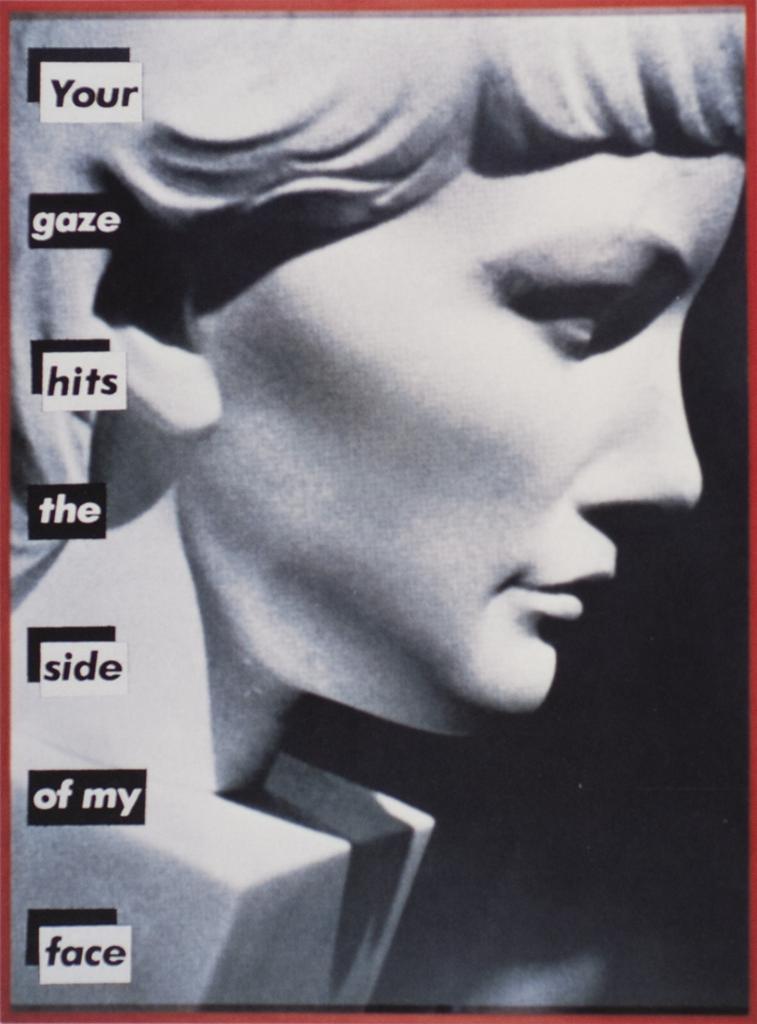

Figure 1. Barbara Kruger, Untitled (“Your Gaze Hits the Side of my Face”) (1981), Photographic Print.

In feminist theory, the male gaze refers to the power dynamic by which men look actively as spectator and subject, while women are looked at as the object. The theory belongs to a larger discourse about pleasure, desire, and power. The theory of the gaze has been approached and studied in multiple ways throughout art history. Learning how the concept of the gaze has been studied is significant because it lays the foundation for how postmodern feminist theorists approach the male gaze in particular. For example, film theorist Laura Mulvey introduced the second wave feminist concept of the male gaze as an aspect of gender power in film. Mulvey addressed the male gaze in her 1975 article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she analyzed how the patriarchal unconscious has structured cinematic form. 1 Mulvey states that women are objectified in film because men are in control of the camera, and cinematic viewing is an interplay between narcissistic identification of the ego and erotic voyeurism experienced by the male viewer.2 The man emerges as the dominant power within the created film fantasy, and the woman is passive to the active gaze of the man. Mulvey further argues that the power to subject another person to the voyeuristic gaze is turned on to the woman as the objectified, thereby justifying male power and establishing female guilt.3 The woman’s presumed passivity does not render her insignificant, however. To account for the privilege imbalance between men and women, Mulvey argues for the female gaze to be seen as equal to the male gaze; women see themselves through the eyes of men, contributing to the patriarchal order.

What happens when this power and control of the male spectator is threatened or questioned? This is a question posed by Barbara Kruger in her work The Gaze Hits the Side of my Face (1981) [Figure 1]. Kruger deals directly with the sexual politics of images. 4 She manipulates photography by displacing the traditional and dominant mode of representation through re-appropriation. 5 Kruger uses familiar and popular images that could be perceived as stereotypical, and juxtaposes them with captioned critiques. Through this process, Kruger creates new relationships between “male-view” (gaze) images and “women’s texts.”6 The assumed viewer is no longer male but includes female viewers as well.

In Untitled (“Your Gaze Hits the Side of my Face”), Kruger challenges the idea of women being the objectified Other [Figure 1]. This black and white photograph depicts a marble bust of a woman looking to the (viewer’s) right. By depicting an image of a marble bust, Kruger places the subject (a woman) as an object. In that moment, the woman is left vulnerable and powerless; thus, the power of the male gaze is heightened. 7 The inclusion of the text “your gaze hits the side of my face,” however, provides the woman with a voice, and allows her to confront the male viewer to disrupt his previously uninterrupted visual pleasure. As Massako Kaminura writes, “Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face successfully attacks the patriarchal culture’s way of seeing women as sex object; it is an assault on both fetishism and voyeurism.” 8

Laura Mulvey states, “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.” 9 In Untitled (“Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face”), Barbara Kruger addresses this imbalance by no longer depicting the woman as passive and instead confronts and threatens the male gaze, returning the power to the woman. Her work allows for the gaze to be longer ideologically synonymous with “male.” Through the manipulation of photography Barbara Kruger challenges the assumed dominance of the male gaze.

Footnotes

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford, 1999), 833.

- Margaret Olin, “Gaze” in Critical Terms for Art History: Second Edition, eds. Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 321.

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” 841.

- Masako Kamimura, “Barbara Kruger: Art of Representation, We Won’t Play Nature to Your Culture,” Women’s Art Journal 8 (1987): 40.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kamimura, 40.

- Ibid., 41.

- Mulvey, 836.