Authenticity

Sarah M. Estrela

Figure 1. Ai Weiwei, Colored Vases (2014) with Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) in the background. Installation view, Perez Art Museum Miami.

The authenticity of a work of art potentially means a variety of things, depending on a viewer’s assumptions and prerogatives. Some viewers prioritize the accurate dating of a work and/or establishing attribution (i.e., an “authentic Jackson Pollock”). Others may be more concerned with cultural authenticity, which maintains that a work can only be considered “authentic” if it was created in the same setting in which the formal and technical traditions informing it originated (or created by a native artist who preserves the same traditions). For example, in order for a Fang sculpture to be deemed authentic, the attribution would have to assume its artist followed traditional models protected from Western influence, and that it originated in Gabon, Cameroon, or Equatorial Guinea. Both notions of authenticity are valid and are not mutually exclusive. While the cultural traditions that inform a work of art have an origin, the standards by which authenticity is determined are in constant flux (like tradition itself) and cannot always be strictly determined.

The concept of originality often overlaps with authenticity. As Richard Shiff writes, “Originality implies some sense of coming first or doing first, a priority or lack of precedent; it therefore cannot be divorced from considerations of chronology and historical sequence. It is also linked to issues of class, a kind of social priority or lineage (one inherits class status and property, just as one does an artistic tradition).”1 Thus, authenticity is ultimately determined by a set of factors that may become divorced from the jurisdiction of the artist: whether the work follows an originary model or is the only one of its kind in the world, the standards for establishing authenticity depend on context and are ultimately subjective.

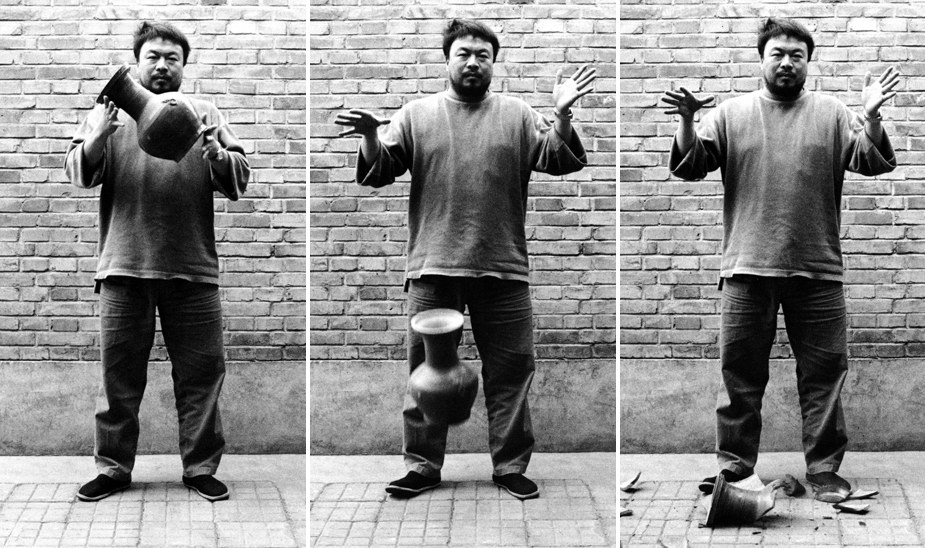

The cultural impact and financial worth of a work of art both depend on its perceived authenticity. The contemporary Chinese artist/activist Ai Weiwei often appropriates traditional Chinese art, transforming pieces that would normally be preserved for historical posterity into new works that generate additional meanings, quite separate from those given by its initial creator. Ai’s Colored Vases (2006–2012), consists of 5,000 year-old traditional Chinese Han Dynasty vases dipped in vibrantly colored paint, valued at approximately one million dollars each on the basis of their authenticity [Figure 1]. They were displayed as part of an installation for the exhibition “Ai Weiwei: According to What?” at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) from December 2013 to March 2014. The vases were displayed directly in front of a well-known photographic triptych, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) which is a frame-by-frame capture of the artist dropping a traditional Chinese urn, which smashes into tiny, unrecognizable fragments [Figure 2]. His work, a conceptual attack on the sacredness with which works of art are imbued over time, is authentically his. Although the urns were not physically created by Ai, his idea to transform them into something else is a work of performance art. The urns themselves embody the sacredness of tradition and age, while his photograph of their destruction conveys the importance of breaking from tradition. The vases and the triptych displayed behind them validate the notion that this figurative (and literal) break is an authentic reaction equally worthy of preservation.

Figure 2. Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), Triptych of three gelatin silver prints, 49 5/8” x 39 1/4” each, Private collection, United States.

This installation was at the center of an enormous controversy when it was displayed at the PAMM. On February 16, 2014, a local artist named Maximo Caminero picked up a peach and green vase and smashed it on the floor, re-performing the act captured in Ai’s photograph displayed just a few feet away. According to reports, Caminero deliberately smashed the vases to protest what he saw as the PAMM’s prominent preference for international work over than that of local artists. A New York Times article revealed that Caminero believed “his destruction of the vase was ‘an act of solidarity with Mr. Ai’ to draw attention to his difficulties as a dissident with Chinese authorities who have barred him from traveling abroad.”2 He elaborated further in a personal e-mail to Ai, stating that “he shared the Chinese artist’s battles ‘as though they were my own.’” This incident draws special attention to the issue of establishing authenticity: while Ai Weiwei is celebrated by the art world for this break from tradition and consistent institutional critique-turned-protest, Caminero is seen as a vandalizing criminal. Intention, technique, and context are thus put to the forefront of a larger debate about originality and legitimacy. Caminero’s subsequent arrest and conviction of criminal mischief essentially declares that Ai’s status as an internationally recognized artist allows him a wider degree of freedom than a local, Miami-based artist.

This case raised several complex questions about the notion of authenticity. Authenticity of provenance is, of course, crucial to the proper identification of a work of art; likewise, cultural authenticity can be seen as a pandora’s box that brings forth questions of geographic origin, validity of attribution based on racial/ethnic/religious identity, and artistic intent. The destruction of Colored Vases brings up an often overlooked question of what can be considered “authentic art.” Is it determined by the artist’s fame? Is it the ways in which something is made or the context of creation? When trying to determine the authenticity of a work, it is crucial to consider all of these questions. Most importantly, however, it is crucial to determine what biases factor into this determination of authenticity in the first place.

Footnotes

- Richard Shiff, “Originality,” in Critical Terms for Art History, Vol. 2, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 145.

- Nick Madigan, “Man Gets Probation in Attack on Ai Weiwei Vase,” New York Times August 13, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/14/arts/design/man-gets-probation-in-attack-on-ai-weiwei-vase.html